Sometimes it's a little hard to tell the difference between night and day in the Terminal Tap.

There's a little window in front, of course. And sometimes, on summer nights, the door is propped open to the street. But from 9:00 in the morning to 11:00 at night, open to close, it's all the same: one room, a door to the store, stale air, too-bright ceiling bulbs, and the mumbled half-sentences of drunks. Not to mention the pool table that's seen better days, a bartender that's seen better days, and a heavy-set man or two passed out on the bar.

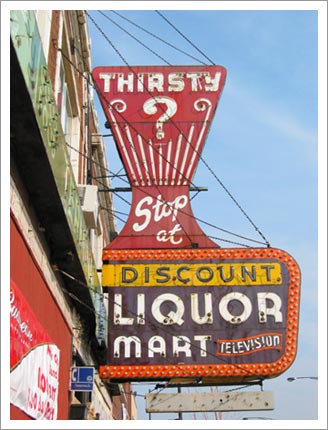

Then again, the customers inside the Terminal Tap probably don't care if it's day or night -- they're just there to drink. Or, from the looks of it, to pass out and forget. After all, no one even knows what the real name of the place is. Even the huge sign that hangs over the sidewalk out front like some kind of Damocles' Sword waiting to pop off its rusty hinges doesn't state a name, but poses a question instead: "Thirsty?" it asks, surrounded by broken neon. Another faded sign right below says "Discount Liquors," while a third proclaims "Terminal Tap - Home of Edelweiss Beer."

Fig1. Doesn't this sign make you want a drink?

Even the dark-skinned man behind the counter on the liquor store side seems confused. "It's called Thirsty Liquors," he says, not very convincingly. The old Polish woman behind the battered bar answers the same question with nothing but a blank stare, the twentieth or so cigarette of the day dangling from her lips. And if you ask the patrons who sit on the few available bar stools that aren't broken, all you get in return are sullen or uncomprehending looks.

That's because the Terminal Tap -- or Thirsty's, or whatever it's called -- isn't the kind of place where you go for friendly conversation, the latest microbrew, or a fine martini. Instead, it's the kind of a place where the floors look like they haven't been washed since Truman was president, you don't use the bathroom if you don't have to, and asking too many questions is more likely to get you a punch in the mouth than useful information. Better known as a "tap room," the faded brown clapboard building attached to a liquor store up on north Milwaukee in Jefferson Park exists for one purpose and one purpose only: drinking. No one goes to Thirsty's to socialize.

Tap rooms are, almost by definition, the lowest of low on the drinking establishment food chain. One step below the dive bars young urban professionals love to slum in and two steps below the worn but friendly neighborhood tavern on the corner, they occupy a little-noticed segment of the liquor industry: that of the scruffy, leftover gin joint in a city that was once filled with them. As taverns attached to -- or sometimes right inside -- liquor stores, there's little confusion about their purpose or pretense. Just as no one ever enters a liquor store with anything but a cold six-pack or a bottle of wine or something harder on their mind, no one picks a tap room for a first date, or to wish a departing office colleague farewell, or to scope out members of the opposite sex. Tap rooms, even the nicest ones, are about drinking and nothing but. Which makes them, in this day and age, something of an anomaly, if not an outright anachronism.

Fig2. A beer's eye view of the tap room register.

Chicago has more tap rooms than any other city in the country, hands down. Whatever liquor store/tap room combinations that might have existed in cities big and small across the Midwest are mostly gone now, but a number have managed to hang on in Chicago despite changing demographics and increasing social stigmas. There are at least 15 or 20 of them scattered across the North and Northwest Sides alone, hidden behind racks of dusty bottles of whisky and crates of creme de menthe mixers or on the other side of a dark door beyond the beer coolers that opens up into a world of taped up bar stools, cracked wood paneling, and $1.25 schooners of Old Style.

As far as anyone can tell, such places are holdovers from the days when factory men and butchers and tradesmen would get off of trolleys and look for a quick one someplace where they could also pick up a bucket of beer to go before going home to the family. Back in the first half of the last century, liquor retailers rarely sold much more than beer and perhaps a couple of different hard liquors, with beer the drink of working class and ethnic alike. Looking to capture any slice of market share they could in a cutthroat business, brewers worked to persuade corner shops to find some way to get a couple of more drafts in their customers after their shift was over and before home-life put some kind of brakes on their pocketbooks. In the wide-open environs of an earlier Chicago, before the 1960s and 1970s turned many working-class neighborhoods into psychological backwaters or ports of entry for new immigrants, few questioned the propriety of having a slew of places a hard-working man could get a drink, no matter what the set-up was like. Cutting a store in half and adding a bar or chucking out the racks of bread and detergent and setting up a tap raised few eyebrows at either the liquor commission downtown or in the bungalows up the street. As the years wore on, however, no one got off trolleys anymore, and tap rooms became the province primarily of those with a memory of how it used to be and no compunction about why they were there in the first place -- mostly older men, whiling away their days, lost to the world of useful work, or their neighborhood, or their church. Or their families, or themselves.

Chances are, you couldn't get a license to open a tap room in this day and age even if you knew all the aldermen in Chicago by their first names, had them over for dinner and stuffed fat envelopes of cash in their breast pockets for dessert. Chicago doesn't like "drinking establishments" anymore, and certainly not ones so nakedly devoted to their purpose. Few things are harder to secure in this town than the legal right to pour someone a beer or a whiskey on the rocks -- it just doesn't fit with the "tourist and family-friendly" image City Hall wants so desperately to project. In fact, you better serve food in Chicago if you want to start selling alcohol, and the more food the better. Meanwhile, don't be located near a school, or a quiet residential street, or end up in a place that had problems with the police in the past, even if you've never even met the previous owner of the building you're now operating in and threw every single old customer out on their ear the day you changed the name on the sign. Chicago's that tough for tavern owners, which means anyone who proudly displays a newly-won liquor license would do well to make it seem like drinking alcohol is nothing more than an afterthought.

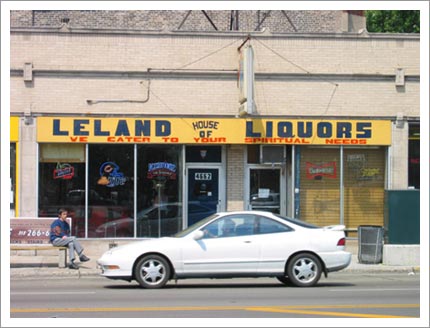

Fig3. "We cater to your spiritual needs."

Why, then, would anyone want to drink in a tap room? For one, it's cheap. A schooner of beer -- one of the big glasses that flares out to practically the width of a hand from its wine glass-sized stem -- costs as little as $1.50 in some places if you're not too particular about your brand of beer. Mixed drinks, when they get made, have a tendency to cost the same as when the faded hand-made price lists on the wall were fresh and new -- a vodka tonic in Fischman's, for example, is still around two bucks. Plus, a little money can usually go a long way. For a place that doesn't look to turn over the monthly rent on every bartender's shift -- or on every customer -- there's a certain lackadaisical relationship between the time you can order a drink and the time you can finish it, an unspoken agreement of sorts between bartender and customer that says "you can stick around as long as there's still a swig left in your glass or a dollar in your pocket."

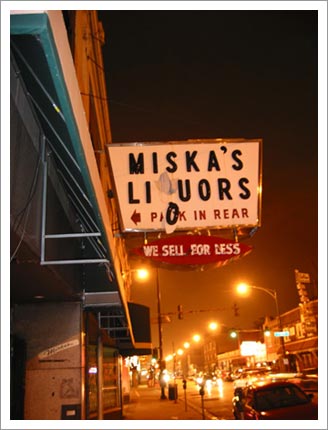

Then again, there's the hours. Unlike other places that time when they're open to the periods when regular workers are off the job, a tap room often fails to make such distinctions. While opening up at 7:00 in the morning (like Miska's on Milwaukee does) might not make much sense from a business-school textbook perspective, it does if you've got the same three guys sitting on the same three barstools by 7:15. And if your core clientele hasn't stayed up past 10:30 at night in a couple of decades -- or can't ever seem to last past 6:00 p.m. before passing out on the bar -- a 2:00 a.m. close just means the bartender has to open back up again five hours later.

But for most tap room habitués, it's probably the anonymity. Sit in enough Chicago tap rooms in 2003 and you're bound to get a sense of what it's like to not have a well-defined, easily grasped place in society these days, or to be viewed on some level as expendable and not worth noticing. You can read it on the faces of the men who, while not alcoholics, still feel compelled to claim the same bar stool every afternoon more out of a sense of ownership than obliteration. Or for, if nothing else, the assurance of a guaranteed "hello" and a "what do you want?" You can see it, too, in the body language of the young Eastern European house painter, sitting in the back of somewhere on a day when his shift ends early, nursing a beer and a couple of unpleasant thoughts about some recent decisions in his life. Or in the laughter of the well-past-her-prime matron, no doubt widowed by now, who has the same number of cigarettes, Miller Genuine Drafts and Illinois lottery tickets every Friday, just around the time the mail has come and gone. Or a dozen other faces, avoiding eye contact, perhaps, or talking to no one in particular.

Staring at your beer for hours on end on a weekday afternoon has its problems, but it can have its privileges, too, especially if you don't have any other particular place to be. Tap rooms, like neighborhood taverns or what used to be known colloquially as "old man's bars," offer up the illusion of both activity and community, even if they are of the mostly empty kind. In a world that offers few places to congregate for those with nowhere else to go, let alone while away some hours free of commercial pressures and "community standards," tap rooms and their brethren provide an oasis to those who just might not have a future as bright as their hopes or their past. The fact that most tap rooms, hidden away behind liquor stores or so long established that they've become a part of the landscape, escape notice from all but their intended customers comes as no surprise, either, and is most likely a primary reason why they're still around.

Fig4. A beer is all the company he needs.

That's not to say most tap rooms are doing anything beyond simply hanging on in a sluggish economy and an increasingly competitive industry. In fact, the number of tap rooms remaining in Chicago is being whittled down almost by the month, with a number of the more well-known establishments having bitten the dust in the last year alone. The Lakeview Lounge, for example, on Broadway and Barry in the city's upscale Lakeview neighborhood, used to sport a faded awning over an entrance that opened exactly in the middle between a 4am bar and a separate liquor store, but closed last year to become the site of a fast food joint and a tanning salon. The Saxony Liquors & Lounge, on Lawrence Avenue between The Green Mill and the L stop, has now gone decidedly upscale: where once the windows were so dirty you could barely see in from the street it's now all hardwood floors and track lighting and bartenders dressed in black.

Ace Liquors, a tap room on Ashland Avenue near Irving Park, went under sometime last year, too. Ace was a true tap room in that fully a third of its tiny storefront space was given over to a bar, with nothing to separate the two areas other than darkened corner, a television, and a number of potted regulars who would were no doubt turned away from every other bar door in the otherwise upscale neighborhood. For years Ace was two doors down from Ten Cat, a hipster-filled destination for the Lakeview art set, and looked anonymous and out of place at the same time: another darkened sign, like Thirsty's, a check-out counter crammed near the front door with shelves of stale gum and hardened Twinkies, a few noisy coolers along the wall, and beer posters from the days when every beer-pitching supermodel had feathered hair. The place had its own brand of door policy: walk in there with a face hardly weathered from life or clothes a little too new and the bartender took his time in getting to you. If you made it past the ritual of being stared at in turn by every one of the regulars and got yourself a beer, one of the more "friendly" patrons would invariably stumble over to you and, standing too close for comfort and pouring out a mixture of alcohol and sweat all over your freshly-laundered shirt, start up a conversation. Few customers, it seemed, drank at Ace if they could avoid it, including the twenty-somethings out looking for a slice of gritty urban life without having to leave the neighborhood.

While the building it was in is still there, Ace Liquors is gone, now just an empty storefront. In recent years it's been joined in death by other, lesser-known venues: VAS Foremost on California and Milwaukee, an odd-shaped room that never had more than two or three customers at a time; Valuemost, up the street on Milwaukee and Pulaski, the tap room itself boarded up and painted over; and Humboldt Liquors, out on Humboldt and Armitage Avenues. All gone now, victims of changing demographics, or changing tastes, or nothing more than the daily grind of trying to run a hard business in a hard town. Few marked their passing, fewer still mourned them.

But a number remain, waiting for their turn at the inevitable perhaps. Like Fischman's on Milwaukee and Giddings, just south of Lawrence. Fischman's has an oval bar so long and wide it takes up almost the entire space, so much so that if you want to get a spot on the south wall you have to suck in your stomach to squeeze by the row of customers sitting on that side of the bar. Wood paneling, a couple of TVs, and a huge smoke eater suspended from the ceiling complete the scene, along with the same ten or so guys who sit in the same place every day. It seems whoever owns Fischman's must have gotten some money recently, because the decades old neon sign and dirty terra cotta front have been torn down, replaced with an individually-lettered sign that spells out the name of the place on a shiny brick exterior. Doesn't make a bit of difference on the inside, though -- the room still grows progressively darker the further away you get from the window, and it feels inside like not much has changed in the past 50 years.

Miska's is still there, a couple of blocks south on Milwaukee. Tiny place, attached to a not-much-larger liquor store, and kind of friendly and talkative, as tap rooms go. The same five or six guys there every night, yelling at each other to make sure they get their fill before closing time rolls around. A hallway to the men's bathroom small enough to have to duck, with the ladies' out the bar, through the liquor store itself and all the way in the back. And Crown Liquors, further down on Milwaukee in Logan Square. Hispanic now, cowboy hats and dirty work shirts and $2.00 Budweisers, with English about as alien as pink jello shots. Up on Lawrence Avenue there's Lawrel Liquors and Tap which has its own parking lot, a relative luxury, and a couple of loud drunk guys with few teeth and a lot of attitude pushing each other around the lone pool table stuck in the front window. L&P, at Lawrence and Pulaski, never has more than two or three people in it at a time, boarded up windows facing the street and a small, frightened-looking Eastern European girl at the cash register in front.

Fig5. Miska's sign has seen better days, and so has some of its clientele.

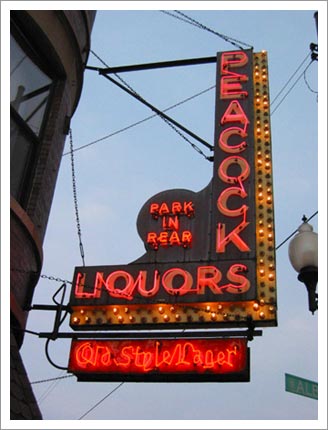

Over on Diversey there's Dorothy's with its bar smack dab in the middle of the store itself, bright lights and all, holiday decorations year 'round and a decidedly cold shoulder feel for the newcomer. Peacock Liquors on Montrose in Albany Park is bright and shiny, a prince among tap rooms, with Serb contractors unwinding after a hard day of work and the same husband and wife running it for 26 of its 60 years. For the kids there's Bruno and Tim's on Sheridan, full of just-turned-21 Loyola students, a Northwestern professor or two, and almost nothing between the bar and the liquor store other than a couple of stacked-up mixer bottles and an outdated calendar. There's one on North Western around Lyndale, another out by Higgins and Harlem on the way to O'Hare, a couple more on Armitage Avenue -- tap rooms all, along with a handful of others that dot the city, nondescript and hardly noticeable.

At this point, the question of "who cares, really?" no doubt comes up. Why does it matter if Chicago has one, twenty, or no tap rooms? After all, dark places filled with old men staring into their drinks don't exactly do very much for jacking up property values. And nobody needs the convenience of package and tap in the same place anymore, do they?

In fact, in some indirect way we do, if we can only bring ourselves to look at such a convenience in a certain light. Cities are made up of all different kinds of forces, some more attractive on the surface than others, but each important in its own way. And while few would argue about the absolute need for all-around, one-stop shopping for liquor, it's clear on some level these places are still necessary for their communities, if for no other reason than they've been there for decades and make up part of the landscape.

But then again, the same can be said for their customers. Right now, huge swaths of Chicago are increasingly looking like slightly more built-up versions of the suburbs, right down to a median age of about 26, with 2.6 people for every household and wide, freshly paved streets for them to drive on. The work-shopping-entertainment troika that for so many years was self-contained in every neighborhood that had a major commercial strip has become increasingly fragmented and distributed in our ever-changing, increasingly mobile communities. In contrast, taverns and their tap room brethren have long played an important role in anchoring urban communities by providing a form of entertainment along with a critical social function, all the while acting as a kind of mile-marker for the residents of the communities they were located in -- even if the tavern or tap room in question was just down the street.

Fig6. Peacock Liquors, a prince among paupers.

The bartender and owner of Peacock Liquors on Montrose is a good example of this. With his wife behind the cash register on a recent day, he has taken up his place behind the bar like any other working day. As he stands there, his weathered face settles into a seemingly impenetrable look of concentration that suggests that behind the placid stillness of his bar, something much more sinister is amiss if he could only figure it out. A quick look around, however, shows everything seems to be in its place: the blond wood paneling somewhere between an Alpine hunting lodge and a suburban American basement, the multiple Beck's bottles in front of a regular customer, the older man with a beer belly and an open-necked shirt holding court in a corner among a group of contractors just off the work site, and a television with the sound turned off showing a rerun of The Hughleys. But maybe the problems he's looking for are right there in front of him -- after all, the guy the next bar stool over is intently looking at a piece of folded up paper before calling the same number on his cell phone over and over, and the contractors' talk over in the corner has suddenly degenerated into a spate of heads nodding in disapproval over something or other. At the same time, a young Hispanic guy comes in holding up a couple of flashy shirts on hangers and a forced smile. "Does anyone want to buy some nice shirts?" he asks in what little English he seems to have worked out. Finding no takers, he thanks everyone in a shy, head-nodding way before practically backing out of the place, turning around at the front door just in time to avoid seeing the knowing smirks and glances start up among the contractors.

A little while later, after The Hughleys has turned into The Jeffersons and the owner's wife has wandered down the sidewalk to visit the neighbors, a young Mexican girl comes in, not older than 21 or 22, with tight jeans and dark hair spilling down her back. The bartender looks up and walks over to the counter that holds the cash register like he's probably done a million times before in his 26 years tending bar. Words are exchanged, barely audible, and her hand reaches into her pocket to find a couple of crumbled bills and some change. Adopting the same face as he wore a moment ago, he thinks for a moment, reaches into the cooler behind him, pulls four Heineken bottles out of a six-pack, and puts them on the counter. Grabbing some packing tape, he wraps it around the four bottles so they don't clank together, puts them in a plastic bag, and takes everything she offers but the change.

She thanks him quietly and leaves, and he goes back behind the bar to put one foot up on a beer crate and fix his gaze again on the man still fingering the folded up paper.