And then came the expressways. They descended upon the city with their evil efficiency and eminent domain — tearing through neighborhoods, creating barriers where they never existed previously, and making unmovable dead zones that formed separations between communities that still exist to this day. On the South Side, entire neighborhoods were purchased, demolished and literally disappeared as the Dan Ryan was laid through in the mid-'50s — coincidentally missing the majority of the Bridgeport neighborhood, where the Daley family called home. The construction of the "Circle Interchange" where The Ryan, the Eisenhower, and the Kennedy expressways all meet up, wiped out the majority of Greek Town and a sizeable chunk of Little Italy, thus adding irony to this mega intersection's later nickname, "The Spaghetti Bowl." Whereas many of the new Chicagoland expressways seemed to stay close to railroads or canals to reduce their effects on the existing city, a little further north the Kennedy Expressway ripped through the Polish neighborhood that centered around Division and Ashland, totally destroying their beloved Noble Street, sparing only the Orthodox church near Division by jogging ever-so-slightly around it — now cars rush by a few dozen feet away, as if to mock its brush with death.

The construction of urban expressways not only sped up traffic within the city, but they also sped up traffic outward — draining Chicago of the majority of its daytime population as they escaped to the suburbs after 5 o'clock each day. With expressways, a 25 mile car trip from the suburbs to downtown could be accomplished in less time than a 10 mile trip across town on public transportation. Thus the expressways served to destroy the urban fabric in another, less physical way, by providing suburbanites the ability to enjoy the culture and jobs of the city center without having to deal with the "real city" — the neighborhoods and the people that populated them. All this was at the expense of the urban neighborhood dwellers themselves; they were the ones who had to deal with the vast 12-lane bridges towering over their neighborhoods and the eight-lane canyons that cut through them; they were the ones who had to deal with the smoke, noise and smog of the passing automobiles; and they were the ones whose businesses were negatively affected, now that they were no longer located on the "major thoroughfares" into downtown (e.g., Milwaukee Avenue, Lincoln Avenue, Roosevelt Road) as cars leaped from suburb to city center without passing by any local businesses.

Even today as you drive around the neighborhoods that border a major expressway, you can still see and feel the effects of the "urban renewal" construction projects from the '50s. At one point all of these roads once completed the nearly perfect street grid that defines Chicago — two street addresses that were once considered neighbors now exist on different sides of a man-made chasm. As you look down the awkward cul-de-sacs, odd dead-ends, fragmented streets and front yards that face on-ramps, you can almost envision the missing homes, neighborhoods and livelihoods that were lost to "eminent domain" highway construction.

The sad fact is that urban expressways don't really serve the city dweller. Sure, you may use it as a quick shortcut to hop down a few exits in the evening, but during rush hour and the weekends they're so clogged you're better off going local. And since they are all coaxial to the Loop, you can't really effectively use them to cross-town. Plain and simple, they were good for one thing only — getting in and out of the city center in the most efficient manner possible. They helped enable the "urban vacuum" that over the course of a decade sucked hundreds of thousands people out of Chicago neighborhoods and spewed them all over the suburbs to create what we now call greater Chicagoland. Inner-ring urban neighborhoods were left to age, as exurb after exurb spread outwards, filling every last bit of open space and, ironically, erasing the open-ness the suburbs were meant to provide.

Our way of life has been so greatly affected and influenced by these massive right-of-ways of convenience that they could never disappear. While funds for public transportation dwindle, highways always seem to be growing and spreading to accept the massive influx of automobiles that increases every day. In fact, even as government funding for the CTA diminishes to the point where it's at risk of shutting down, it's impossible to imagine the same lack of funding could ever befall upon the expressway system, where constant construction and improvements keep many an IDOT worker busy with something to do.

But the deed has been done — Chicago bears the scars of the great American urban expressway, and these are scars that we must learn to live with. I'm optimistic, though — I believe the best characteristic of a city is its infinite adaptability. What may appear to be a disadvantage to some becomes an opportunity for others. Old buildings find new leases on life with new uses. Formerly polluted waterways become desirable real estate. Neglected neighborhoods become affordable opportunities for rehab. And so I look at the bottomside of a freeway as it passes through a neighborhood and see opportunity. How can we erase the expressway's status as a boundary creator? How can ease their aesthetic from an "offensive eyesore"? How can we creatively reuse this wasted space?

Some cities have chosen to take action against the blight that is the urban expressway. Boston decided to push I-90 underground into a tunnel for its right of way, in its infamous "Big Dig" project. This massive project took more than two decades to complete, but is now finally allowing the renewal of the neighborhood above, where the old elevated highway infrastructure that originally displaced more than 20,000 residents is being removed. Even here in Chicago there are proposals for more seamless blending of the expressway into the city. In Oak Park, the citizens drafted a plan called "Cap the Ike" that would build "land bridges" over the Eisenhower Expressway, linking the two halves of Oak Park together with new strips of parkland. Not only would this unite the village that was split in half by the Ike, but it would also reduce the high levels of air and noise pollution that urban expressways inherently cause. Lastly the Chicago Architecture Foundation recently commissioned a conceptual proposal for the downtown stretch of the Kennedy where the expressway cuts below the street level. In these proposals, pedestrian footbridges are mixed with urban parks and private buildings to patch the canyon created between the Loop and the West Loop neighborhoods.

All of these proposals are based on a highway that cuts below street level, but what about areas of the city where the expressway towers above, like the Dan Ryan through the South Side, the Kennedy in the Northwest, or the Stevenson through the Southwest? In these areas massive cement pylons hold the expressway anywhere from a few dozen to a hundred feet above the neighborhood below. These urban caves are severely underutilized — the most common uses I have seen have been storage of construction equipment and shipping trailers or by the homeless, who set up elaborate camps to be sheltered from the elements. The gaps between the girders are a perfect size to create a small apartment — room for meager bedding and a place to store personal belongings in trash bags. Obviously this use is not one advocated by the city, so fences are erected to keep the homeless out — but why should we prefer abandonment over productive use?

My proposal is to make use of these spaces, to build within them, and bring business, culture and life to these utilitarian structures. The following three "concepts for creative reuse" use the Kennedy viaduct over North Avenue as a point of reference. The Kennedy expressway acts as the official border between Chicago's near Northwest and North Sides, and in this neighborhood, clearly defines the eastern boundary of Wicker Park and Bucktown. The highway viaduct creates a well-defined border that discourages foot traffic. A distance that would normally walked within a neighborhood suddenly becomes a bus or car trip when it passes under the Kennedy. What if we could bring some interest or draw to this dead space and actually attract people to pass through the neighborhood "borders?"

Concept 1: The Underpass Gallery

Click on the image or here to see a larger version.

This first concept takes a formerly lifeless highway underpass and brings a dynamic photo gallery to its underside. Undulating walls would be built to create small inlets, and within these small spaces LCD screens are securely mounted and protected from theft and vandalism. These screens could be hooked up to an Internet image feed, such as Flickr, so that both artists and amateurs could simply drop their photos into the group pool and get them displayed instantly in the physical environment. These photos would cycle and change over a short time span and in a random order, so that the walls are different each time you pass through — even multiple times in a day. Showing random photos from the Flickr Chicago pool would be an natural connection to the city — imagine passing by and seeing photos from all over the city, possibly opening your eyes to a neighborhood you had never known was so interesting. What if the gallery focused on current happenings within the city? Imagine passing through this gallery and seeing virtually live photos from the Jazzfest or from the latest art opening. The underpass gallery could open your eyes (quite literally) to events that might not have impressed you on paper, but catch your attention through visuals.

In addition to Chicago-centric photography, maybe the focus could sometimes be more arts based. There could be themed sets, open competitions, or featured artists of the day or week. Other interesting opportunities for use might arise from having dynamically updated LCD screens in a public place, too. Information about local events, plans for future construction in the immediate neighborhood and breaking news updates could be displayed on a specific screen. Local advertisers could subsidize the cost of the underpass gallery through random ad placement within the photos. The possibilities for use are limitless — a dynamic public gallery in a formerly wasted space would bring life and excitement to what was once a boring walk, and could even transform what was once a route to get from A to B into an actual destination.

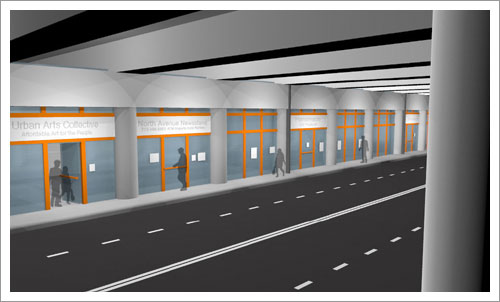

Concept 2: Small Spaces for New Businesses

Click on the image or here to see a larger version.

This concept seeks to provide low-cost storefront space for small, start-up retail businesses. Finding affordable space that is also of quality construction and is located in a highly trafficked area is one of the many initial hurdles for a small local business owner to overcome. The naturally divided spaces underneath the overpass between pillars become affordable storefront rental units. This concept is meant to be flexible and modular: the walls between units would be movable and could be easily opened and closed by the "landlord" as needed. A proprietor could rent as many units as they need with the option to expand as their business grows or as open space allows.

This concept is also meant to shelter niche businesses from the pressures of corporatization and gentrification of retail spaces in traditional neighborhoods. Many small businesses find that they are pushed out by soaring rents when the surrounding neighborhood begins to go upscale. The expressway provides a "stable" neighborhood structure that is not bound to transform radically over the years, thus allowing the tenants to lock in a fixed rent rate and keep their overhead, so to speak, predictable. Although this proposed retail district does not provide storefront parking, it does provide high visibility for both auto and foot traffic. However, a store located in the underpass strip could effectively target those who walk or use alternative transportation. For example, a bicycle repair service would benefit from the high bike traffic on a major thoroughfare, while a bag boutique might cater to people who walk and have a need to carry groceries or other items. Units that are not initially leased or are between lessees could be temporarily rented for other uses, so as not to have empty storefronts bring down the perception of the other storefront spaces. Other uses for under-leased spaces might include meeting spaces for community groups, high profile studios for artists, non-profit or charity publicity, or temporary storefronts for fundraising by local groups. The goal of these spaces is not to create the next hot shopping strip, but to give beginning business proprietors an affordable and modular way to start selling their wares to the public through a high profile storefront.

Concept 3: The Alternative Transportation Center

Click on the image or here to see a larger version.

When the Blue line meets up with the Kennedy and runs down the center, the CTA stations move to the middle of the highway, with the station entrances in the overpasses below. Although I believe that El stations are better suited as the central transportation point at the center of a neighborhood, I also believe that El lines that parallel highways provide a necessary alternative to driving the same route. This concept incorporates other forms of alternative transportation alongside these CTA stops to create a central hub between them all. The El station anchors the hub, providing convenient access to CTA bus lines, the iGo car-sharing service, and secure bike rental/lock-up service. This concept imagines the North Avenue viaduct as a subway stop for a CTA "Circle Line" (proposed in my previous article) as it runs from Division/Ashland on the Blue Line to North/Clybourn on the Red Line. When subway riders exit the station to wait for the North Avenue bus, they are sheltered from the elements by the overpass above — the ultimate bus stop canopy!

Bike rental would be available at the same hub, allowing anyone with a credit card to swipe it through an automatic lock system to "check out" a bike for a modest fee. This service could be treated a lot like a movie rental service; you apply to be a member, and once you are accepted you get full bike rental privileges. The bicycles could be returned at any location for maximum convenience, and could be reserved ahead of time via an interactive website. Additionally, this same rack could be used as an "ultra secure" bike rack for personal bicycles as well. Instead of bringing your own lock, you could swipe your credit card and for the cost of a parking meter, use an indestructible bike rack lock that will only open if the users credit card is swiped for identification. The bike center could be manned with a single employee for assistance in rental and using the auto-rack, as well as providing extra bicycle security and peace-of-mind to the users.

Lastly, the spaces between cement pillars are a perfect size for iGo car garages. Currently the cars are located in the heart of the various neighborhoods they serve, but bringing additional cars to a central transportation hub would provide easy connection from CTA lines, as well as instant access to the Expressway above. The garages also protect the cars from vandalism, weather, and also provide a sheltered space for users to load and unload. Locating these iGo garages in such a high traffic area also advertises their presence and might encourage more people to use the service. Now instead of the underpass being merely an area to pass through on the way to the other side, it becomes a hub for alternative transportation, giving options where once there were none.

Implementing these concepts obviously would not be easy — lots of bureaucratic red tape and liability issues lie in the way, but I don't think they are impossible concepts. The automobile is deeply ingrained in the American lifestyle; the expressway overpasses that tore through Chicago in the mid 20th Century are not going away anytime soon. However, creative reuse of wasted space is what helps make Chicago and other urban centers such exciting places to live. I believe that if we make use of the "dead zones" created by these overpasses we can bring life and activity to these dark and dirty spaces. In doing so, Chicago could suture the gashes that the expressways have left us, and ultimately bring long-divided neighborhoods together once again.